How many times have you been watching a crime drama where the detectives find some genetic material then within minutes they’ve caught their suspect? We’ve all seen it, but the reality of how things play out is more nuanced and certainly much slower than Netflix would have you believe.

In the significant majority of alleged crimes, no genetic material is collected at all. Moreover, in instances where genetic material is collected, there are numerous reasons why the investigating agency may have trouble locating a person who “matches” their sample. So in order to give a better understanding of the use of genetics in criminal investigations, I’ll go over 1) when genetic/DNA evidence is collected, 2) address the challenges with proper sample collection/storage, 3) discuss how investigating agencies go about finding a match for the genetic sample, and 4) elaborate on some of the challenges of using genetic evidence. As they say, the devil is in the DNA.

Types of Cases Where Criminal Investigators Collect Genetic Evidence

DNA evidence can come from various sources such as blood, saliva, semen, skin, and hair that are taken from the root (recent advances in technology suggest that non-root hair may be viable for DNA analysis in the future). As such, police agencies will routinely collect genetic material in cases that involve serious violent crimes to determine the identity of possible suspects. For example, in instances of rape and other types of sexual assault, the police will attempt to gather DNA evidence from the alleged victim’s person, property, clothing, and from other items that may have genetic material on them. Similarly, in homicide and other violent assaults, the police frequently gather

potential genetic material like the blood that may be at the crime scene. In some limited circumstances, the police may even try to collect genetic material from property crimes such as a home burglary where the suspect was cut by the glass while entering through a window.

On the other hand, there are far more instances where the police will choose to forego the DNA collection process. It would be extremely rare for a police agency to show up to the scene of a bicycle theft, iPhone grab-and-run, or vandalism and then immediately bring out a forensic team to start swabbing for genetic material. Furthermore, most crimes are not serious violent crimes – most are not even felonies. By some estimates, low-level misdemeanor crimes outnumber felonies by as much as 4 to 1.

The Challenges With Proper Genetic Sample Collection and Storage

Now, just because the police have collected DNA evidence does not mean they have a “Go to Jail” card.

In fact, the collection of DNA may not have been successful at all. Here’s how it typically goes:

- the police response to the crime scene;

- the police enter the crime scene in an attempt to figure out what happened;

- once they have a sense of what occurred, they try to secure the scene to preserve the scene (this is where the yellow tape comes in handy);

- other police come to the scene so the police staff can divide who does what;

- they begin looking for evidence and identifying where genetic

the material might be; - a police officer or civilian staff will swab areas with

potential DNA; - after the sample is collected, it has to make its way to the police station to be checked in for evidence.

Even after going through the process above, the swab with potential evidence may not have anything on it that is able to be tested. Moreover, there are times when genetic material is collected but the quantity is not enough for a lab to test it. Here’s the kicker, things can go wrong at each and every one of those steps – the alleged victim may have inadvertently washed away the suspect’s genetic material, the responding officer forgot to wear gloves, other non-police civilians tampered with the crime scene, there was a delay in booking the evidence, etc. (and this is just a small sample of potential issues).

Most significantly, all of these potential issues can pop up before the sample makes it to any forensic lab…

How Investigating Agencies Find a Match for Genetic Samples

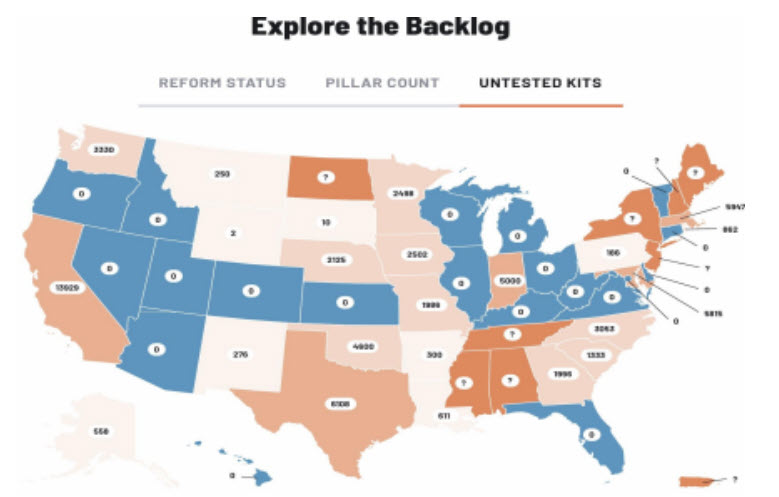

A genetic sample making it to the police station’s evidence room is only the beginning of an oftentimes long process. In order to associate the collected genetic material with a potential suspect, they must have the sample sent to a forensic laboratory for analysis. As discussed above, there are relatively few cases where genetic material is collected; more significantly, of the cases where supposed evidence is collected, there are hundreds of thousands of samples that are not tested whatsoever. “Rape Kits” are frequently used to collect genetic data where sexual assault is alleged, but some estimates put the number of untested kits at over 100,000. In other words, the police went through the arduous process of collecting DNA evidence but then never sent it to any lab for analysis. The following is an accurate number of untested rape kits as of February 2023:

After a potential genetic sample is sent to a laboratory for analysis, the lab will begin the process of actually extracting genetic information. Naturally, labs are just as likely to find genetic information as they are to find nothing on the submitted swab. Let’s say for argument’s sake that the lab does find genetic material that they can access, then what happens? Well, the lab will submit the DNA profile into their system where it will stay until a “match” is found. Why quotations on the match? Because no forensic lab ever actually matches a DNA sample to a particular person – instead they will conclude that a suspect’s profile cannot be excluded as a potential source of DNA (complicated enough answer for you, huh? Well that’s exactly what the next paragraph is for).

The Challenges to Using Genetic Evidence

DNA evidence is much more limited than it may initially seem. Taken from the point-of-view of the prosecution, they will often attempt to paint the presence of a suspect’s DNA at a crime scene as very strong evidence of guilt. However, the use of DNA evidence is far more nuanced. For example, genetic evidence at a crime scene is not legally considered direct evidence of any crime. At best, a suspect’s DNA can be considered by a jury as circumstantial evidence of the allegation. Taken further, the fact that DNA is at a scene doesn’t relieve the prosecution of its obligation of proving every element of every crime they have alleged.

Imagine for example, that Person A is found deceased from a gunshot wound and Suspect B’s DNA is found at the same scene – what does the presence of DNA actually mean? When considered carefully, the DNA doesn’t say who shot Person A, it doesn’t explain the circumstances before the shooting, it doesn’t say if Suspect B was acting in self-defense, and it doesn’t say if Suspect B was at the scene at any time even remotely close to the time of the shooting. The prosecutor would still have to produce answers to all of those questions, and they’d have to prove it beyond a reasonable doubt.

When viewed with cautious eyes, it becomes apparent that genetic evidence is tremendously complex but oftentimes oversimplified to fit a particular narrative. DNA is a little thing (invisible actually) with big implications. But as with all things, you’ve got to read the fine print.

If you have any questions or want to take to an experienced attorney about your circumstances, Lamano Law Office can help. Contact us online or email info@lamanolaw.com.